Fertilizers and how do they REALLY affect the Earth?

January 7, 2026 | Byron A. Mohammed

Introduction

This blog post, “Fertilizers and how do they REALLY affect the Earth” was created to educate the public on the true implications of fertilizer use, the natural mechanisms within plants, and what you as a citizen can do to minimize your impact and avoid synthetic fertilizers altogether. I recommend you read the sections Takeaways and Asks/Plans for the future for an easier synthesis of this paper.

In science, certain chemical compounds are called “Nutrients” and are defined as macronutrients (this acronym is helpful: C’HOPK’NS) that are required by plants for them to live. This acronym stands for Carbon, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Phosphorus, Potassium, Nitrogen, and Sulfur. Nitrogen and Phosphorus will be discussed in this blog since they are the primary types of fertilizers. Macronutrients and micronutrients are both needed by plants to survive, though macronutrients are needed in much larger quantities than micronutrients often found in the soil in small portions.

Scientific Background

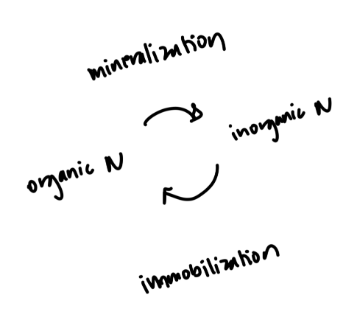

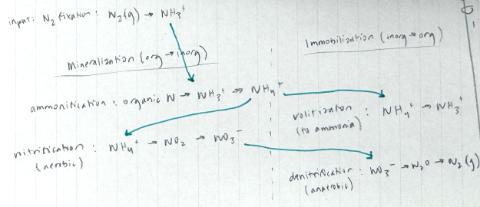

In order for plants to utilize nutrients like Nitrogen and Phosphorus, they often require processes to convert them from organic forms to inorganic forms for utilization, which will be discussed in the section below and shown clearly in Figure 2 below. Nitrogen cycling will be discussed from here on unless explicitly stated. Organic nitrogen can enter the soil system, which consists of approximately 50% pore spaces (containing water (of some concentration) and air (atmospheric makeup equivalent), and 50% solids, whether a mineral or organic component. The water in the soil moves into the plant system through the root hairs, where water (containing minerals) moves from High to Low water potential. Water potential (Ψ) is defined as the “freeness” of water to move, where a high water potential (Ψ = 0) contains no solutes and can be considered pure water, and a low water potential (Ψ < 0; negative) contains plenty of solutes & contaminants and is not readily able to move. Water will move in the xylem tissue of the plant from the root hairs, to the root, stem, petiole, leaf, and into the atmosphere as a gas once evaporated, through a process called Transpiration (Ward & Trimble, 2003). These allow the plants to acquire the nutrients without moving a muscle, literally! However, despite being distributed to the plant cells successfully, only inorganic Nitrogen can be utilized in biological processes for biomass accumulation, enabling enzyme activity, and the creation of proteins, (Broadbent, 1965). A balance between the processes of mineralization and immobilization occurs by microbes in the soil. Mineralization is the conversion of organic, naturally occurring, nitrogen (proteins and amino acids) to inorganic nitrogen (NO 3 - and NH 4 ). And immobilization (Jiang et al., 2025) is the complementary process converting inorganic to organic; see Figure 1 for a simplified understanding, and Figure 2 for the complete process from atmospheric nitrogen (N 2 (g)) back to the atmosphere again by denitrification. N 2 is acquired from the atmosphere by nodules containing rhizobial bacteria, which are a type of soil bacteria that form a symbiotic relationship with the plant family legumes, like peanuts for example.

Figure 1: Balanced process of N mineralization & immobilization between the atmosphere and plants.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of the complex processes of Mineralization and Immobilization. The green arrows demonstrate the order of steps taken to return back to the atmosphere.

Both Nitrogen and Phosphorus are utilized in fertilizer, both of which are vital macronutrients for plant growth and biological processes at the cellular level. These elements exist in forms not available for plants to use immediately. These fertilizers produced by us use forms that CAN be used in cellular processes, or rather, they introduce forms that once introduced to water (dissolution begins) release phosphate ions into the soil water, (Vance, C.P., Graham, P.H., Allan, D.L. (2000)).

These bacteria are the primary mechanism for plants to receive organic nitrogen (conversion of N 2 (g) → NH 3 ). However, humans have devised methods to fix atmospheric nitrogen for the use of fertilizers containing the vital macronutrient required for plants. We utilize the Haber-Bosch process, which is a high temperature and pressure chemical reaction to create Ammonia (NH 3 ) as a by-product. In all fairness, this process is wonderful in the eyes of consumers. Now we have the means to produce fertilizers that’ll increase crop yields for agricultural purposes. However, the altering of the global nitrogen cycle and defined greenhouse gas concentrations WILL lead to massive changes to our global climate system. Not to mention the implications for using massive amounts of electrical energy to complete this process.

Contamination & Eutrophication

Once the fertilizer is applied to single plant fields, whether an agricultural site or your lawn, the lack of diverse plant communities prevents that large quantity of applied nitrogen, not produced by the system itself, will leach downward or move laterally as surface flow runoff. Deep rooting structures and secondary growth of trees collect and utilize added nutrients much more effectively than grasses will. The downward percolation of fertilizer can easily pollute the groundwater system below it. The common perception of groundwater is that the soil above it will completely filter any contamination that moves downward, but that is simply not the case. Often, sediment particles from numerous sediment layers (increasing in compaction as you travel downward) can in-part bind with and find themselves in association with these added chemicals, but in no way does it “filter” an input of nutrients like a coffee filter would filter coffee grounds. Contaminants in groundwater can move either with the flow of groundwater (advection) or by a gradient in concentration (diffusion- moving from high to low concentration, where the point source is always a locality of high concentration). The more prominent mode of transport of fertilizer is on the surface. Sprinkler systems for lawn care, irrigation for crops, and natural precipitation events can all lead to runoff. Following said watering event, fertilizer once in the soil can be mobilized by the rain and travelled downslope into a river. This river flow will find itself moving into a large body of water, likely a lake or ocean. This excess nutrients into a body of water can lead to Eutrophication. Algal blooms, which contain opportunistic photosynthetic bacteria that grow in population rapidly, consuming the added nutrients (Eutrophication) which you may have heard of before. As a side effect of the deaths of the bacterial population, the decomposition of their mass consumes the oxygen in the water column (Anisfield, 2011), leading to very low oxygen remaining, killing vegetation and animals alike. A loss of plant and animal species by the specific cause of human beings is a pressing environmental issue and must be remediated.

Takeaways

● The processes required to convert organic forms of Nitrogen and Phosphorus into inorganic forms, like nitrogen fixation and mineralization, are essential for cellular

functions and energy production in plants

● Humans are able to fix Nitrogen into ammonia for fertilizers, which has its benefits, but it does and will contribute to disruptions in the global nitrogen cycle and greenhouse gas concentrations

● Nutrients may leach into groundwater or runoff into rivers (and into oceans), creating algal blooms and oxygen depletion, significantly harming these ecosystems and their biodiversity.

Asks/Plans for the future, that YOU can participate in:

● Using organic fertilizers or composting can significantly reduce the demand for anthropogenic fertilizers, and reduce the electrical energy and pollution associated.

● Use only recommended amounts of fertilizer; an excess will lead to percolation (downward movement of the contaminant) as well as surface runoff

● Avoid overwatering your lawn. These daily-set sprinklers don’t allow any amount of natural uptake of nutrients; you’re washing it all away.

Bibliography

Addiscott, T. M., & Thomas, D. (2000). Tillage, mineralization and leaching: Phosphate. Soil and Tillage Research, 53(3–4), 255–273.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0167-1987(99)00110-5

Anisfeld, S. C. (2011). Water Resources. Island Press.

Broadbent, F. E. (1965). Effect of fertilizer nitrogen on the release of Soil nitrogen. Soil Science Society of America Journal, 29(6), 692–696. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1965.03615995002900060028x

Gregory, P.J., Wery, J., Herridge, D.F., Bowden, W., Fettell, N. (2000). Nitrogen Nutrition of Legume Crops and Interactions with Water. In: Knight, R. (eds) Linking Research and Marketing Opportunities for Pulses in the 21st Century. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture, vol 34. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4385-1_30

Jiang, W., Du, S., Elrys, A. S., Zhang, J., Cai, Z., Zhang, Y., & Müller, C. (2025). Global climate changes decoupled soil nitrogen mineralization and immobilization. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 109794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2025.109794

Prinz, B. (2000). The Impact of Nitrogen Compounds — A Problem of Growing Concern. In: Yunus, M., Singh, N., de Kok, L.J. (eds) Environmental Stress: Indication, Mitigation and Eco-conservation. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-015-9532-2_10

Vance, C.P., Graham, P.H., Allan, D.L. (2000). Biological Nitrogen Fixation: Phosphorus - A Critical Future Need?. In: Pedrosa, F.O., Hungria, M., Yates, G., Newton, W.E. (eds) Nitrogen Fixation: From Molecules to Crop Productivity. Current Plant Science and Biotechnology in Agriculture, vol 38. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-306-47615-0_291

Ward, A. D., & Trimble, S. W. (2003). Environmental Hydrology, Second edition. CRC Press.