How Urban Heat Islands Work and How It Affects You

November 7, 2025 | Byron Mohammed

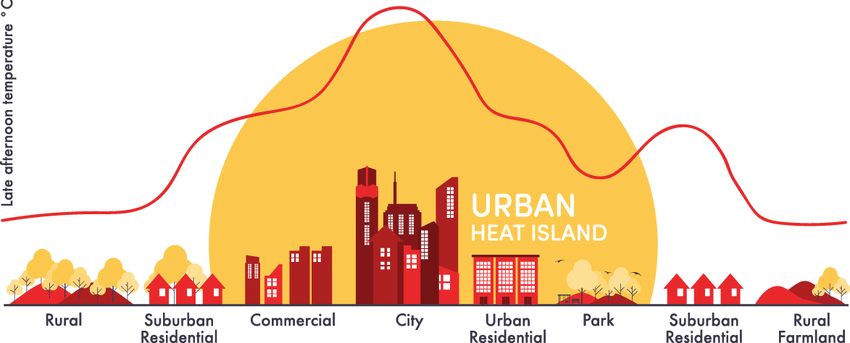

This blog post today is dedicated to the phenomenon of the Urban Heat Island effect (UHI). The “Urban Heat Island” is a term often used in Environmental Sciences that refers to the physical property of the atmosphere above densely populated cities with lots of impervious surfaces, resulting from the urbanization of an area. Impervious surfaces, like man-made concrete streets and buildings, are surfaces that don’t allow water and precipitation to penetrate it, as well as having different thermal properties than that of soil or of vegetation. Water is notable for having high heat holding capacity, and without water on the surface, the temperature is greater, by ~2 to 5 °F or more at night, (Park et. al., 2024). An area with little water content and high amounts of reflected solar radiation can lead to rapid warming. This warmed air at the surface rises, as air does with a lower density, and creates a sort of spherical profile around the city, as shown in Figure 1, (Fuladlu et. al., 2018).

Scientific Background & Explanations:

In the atmosphere, precipitation typically occurs when rising air cools, and no longer has capacity for the moisture within itself, so it simply falls. This occurs when water vapor molecules accumulate and its weight (gravity) exceeds the force of friction below it. If there is a permanent feature of warm air throughout and above a region of human settlement, precipitation will occur mostly on the edges of this civilization. Which, actually may be a good thing in some cases; we may be able to set up farmland surrounding a city for consistent irrigation practices. Though, the Urban Heat Island now secludes the city itself from persistent precipitation; those trees and plants you have in your backyard may receive significantly less rain than they would’ve 30 years ago; or would they if there weren't so many densely packed buildings.

Humidity in the atmosphere acts as a buffer to incoming solar radiation. Water vapor is one of the primary greenhouse gases (GHG), which are effective absorbers and emitters of shortwave (incoming solar radiation) and longwave (radiation emitted by the planet's surface as Infrared (heat)) radiation. Clouds, which are condensed water vapor droplets in the presence of condensation nuclei, significantly increase the albedo of the atmosphere. Water has a high heat capacity, so the presence of water and clouds in the atmosphere creates this said buffer. The Earth’s surface, in theory, emits 100% of the incoming radiation. Though, with the presence of greenhouse gases, an equilibrium point that balances insolation with emission exists in the atmosphere, where shortwave and longwave are balanced at 0 °F, (Hillier, 1989). With more moisture in the air, the 0 °F point rises, causing the surface to radiate more heat to remain in equilibrium with incoming radiation. Specifically regarding urban regions with high aerosol and GHG production, the radiative equilibrium point rises further, causing the surface to warm more significantly at night. Remember; impervious surfaces are solid and absorb energy, with no processes to expend that energy. Surface water allows for incoming heat to be contained in water bodies. Energy is expended through the process of evaporation to excite the H2O molecules to change state from liquid to gas; energy is no longer present to warm the surface.

Most of the agricultural sites in the United States are found Southwest of the great lakes, between Canada’s dry and cold “cP” (Continental Polar) air and the warm, moist air of the Gulf of Mexico, named “mT” (Maritime Tropical). Cold, dense air has a lower altitude aloft, at a given atmospheric pressure, which would be considered a ridge. Warm, buoyant air has a higher height aloft, called a trough. The ridge-trough pattern is also what produces such great agricultural sites; high amounts of precipitation occurring on the exit of an atmospheric ridge. The UHI produced by intense urbanization in the Northeast of the U.S. causes a trough to occur, which explains the locality of the precipitation even further; with precipitation being highest West of urban cities; between cold, dry polar air and warm, moist oceanic air.

Developed soil profiles and diverse ecosystems are very important in maintaining not only the water balance of a region, but the temperature near the surface and aloft. For example, deciduous forests are biologically diverse systems with an established overstory, that provide shade and stability for the system, and with secondary (woody) growth, they are effective photosynthesizers. Trees also greatly improve soil water retention, soil rigidity, and atmospheric moisture. With more water in the plant system, cycling between the atmosphere and the surface occurs more frequently, where the absence of trees will allow water to leave the system as surface runoff, which would be removed from the entire system rather than taken up by plants. Forests also support organic matter sequestration in the soil, with lots of smaller understory vegetation providing food for herbivores and detritivores, as well as nutrient cycling for the trees themselves.

The water in plant cells, water vapor surrounding plant leaves, water in the soil above and below the water table, and the shade provided by leaf canopies considerably reduce the near-surface temperatures. When vegetation is removed and replaced with concrete, not only do the temperatures increase, but the evapotranspiration rate decreases as well. Evapotranspiration is the total water lost from the surface by evaporation, which can occur as free standing surface water or water lost by the process of transpiration, in association with photosynthesis.

Issues Related to UHI:

The primary driver for the Urban Heat Island effect and shape is impervious surfaces of urban regions, specifically cities. With the global population growing steadily, more people migrate to cities. Highly populated cities are excellent places for economic and monetary growth, as well as places for societal opportunities with an upbeat nature and plenty of excursions offered with so many businesses concentrated in one area. Life can be good here!

However, with more people and increasing urbanization of non-urban areas, impervious surfaces increase proportionally. Construction and the presence of concrete completely rewrites the region’s ecology and water budget, leading to irreversible changes to the system, (Ortegren et. al, 2005). I’d like to note that: this isn’t an end-of-the-world phenomena, but it will create very interesting atmospheric morphologies and potentially lead to uncomfortable and nonnatural climates within a city, extremely separate from the regions surrounding it.

Take-Aways:

The Urban Heat Island effect is resultant from the urbanization of ‘rural’ areas, that produce warmer environments with the presence of impervious surfaces that impede natural processes that occur surrounding precipitation, temperature, atmospheric stability, and the water budget. In the future, we need to be mindful of the amount of urban development we do and how it impacts the Earth.

Asks/Plans for the future, that YOU can participate in:

- Preserve our Green Spaces

- Parks and community gardens impact the overall health of the region, where trees provide many hydrological & ecological benefits

- Promote Water Conservation

- Reducing your personal household water usage will prevent an overuse of groundwater (that recharges naturally at a specific rate) and reduce an overproduction of wastewater

- Support sustainable Urban Planning

- Advocate for the use of permeable pavements, tree-lined streets, and bus & subway development to prevent excessive highway and parking lot productions!

- Educate others about UHI

- Telling your friends, family, and community about what you learned can help spread the word about the concrete jungle, and issues behind it, that we all are so used to!

Check out some additional readings:

Ren, Y., Feng, F., Elia, M., Giannico, V., Sanesi, G., & Lafortezza, R. (2025). Understanding the coupling effect of multiple urban features on land surface temperature in Europe. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 105, 128723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2025.128723

Bibliography

CHEN, W., ZHANG, J., HUANG, C., FU, S., LIANG, S., & WANG, K. (2025). Measuring heat transfer index (HTI): A new method to quantify the spatial influence of land surface temperature between adjacent urban spaces. Sustainable Cities and Society, 106268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2025.106268

Estes, M. G., Quattrochi, D., & Stasiak, E. (2003). The Urban Heat Island Phenomenon: How Its Effects Can Influence Environmental Decision Making in Your Community. NTRS, 8–12.

Fuladlu, K., Riza, M., & Ilkan, M. (2018). The Effect of Rapid Urbanization on the Physical Modification of Urban Area.

Guo, A., He, T., Yue, W., Xiao, W., Yang, J., Zhang, M., & Li, M. (2023). Contribution of urban trees in reducing land surface temperature: Evidence from China’s major cities. International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 125, 103570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2023.103570

Hillier, D. J. (1990). An iterative method for the solution of the statistical and radiative equilibrium equations in expanding atmospheres. Astronomy and Astrophysics (ISSN 0004-6361), 231(1), 116–124.

Ortegren, J., Liu, Z.-J., & Lennartson, G. J. (2005). Spatial Variability of Temperature Trends in Urbanized and Urbanizing Areas of North Carolina. The North Carolina Geographer, 13, 31–45.

Park, K., Baik, J.-J., Jin, H.-G., & Tabassum, A. (2024). Changes in urban heat island intensity with background temperature and humidity and their associations with near-surface thermodynamic processes. Urban Climate, 58, 102191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2024.102191