.jpg)

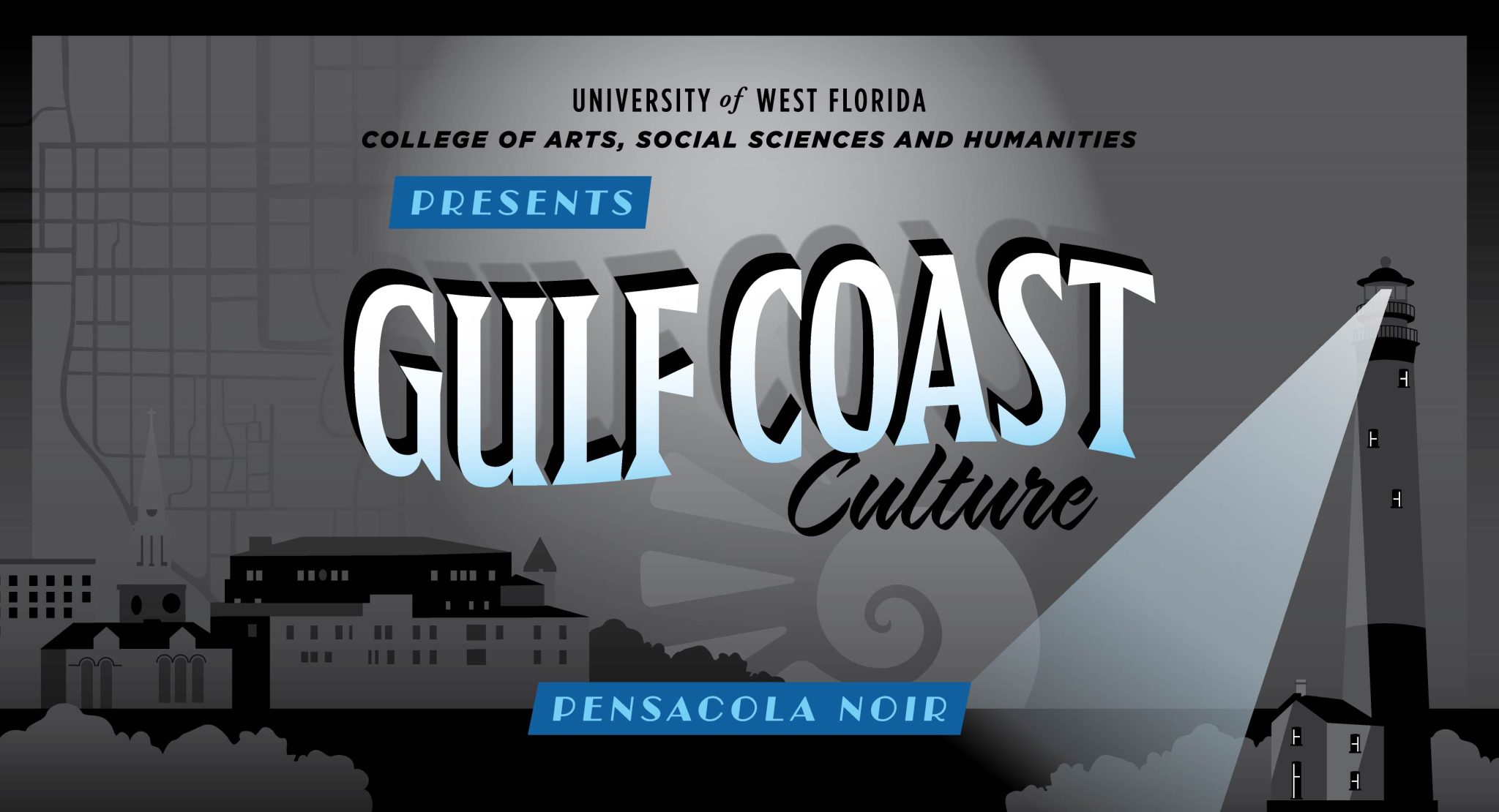

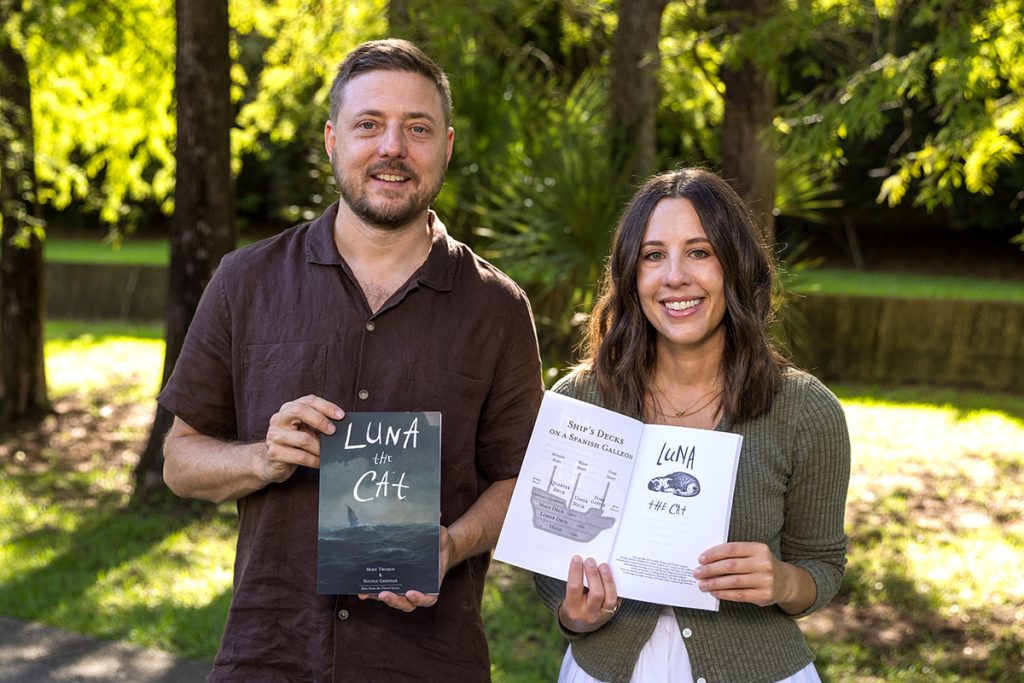

From Theatre and Arts Administration to Business Ownership

Victoria Redig, a successful businesswoman with a wide range of talents, credits the University of West Florida’s College of Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities (CASSH) with helping her build the foundation for her career. Today, she is a partner and senior bookkeeper at The Bookkeeping Firm FL LLC, where she balances the responsibilities of business ownership with motherhood.

.png)

-480x480.JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

-20180330_Honors_Convocation_086.jpg)

DSC05995.jpg)

DSC06013.jpg)

DSC05389.jpg)

DSC05413.jpg)

Germany-Trip-Group-Photo.jpg)

20170123_MVRC_005.jpg)

summer-festival-chorus.jpg)

UWF-50th-Anniversary-Gala_20161116_035.jpg)

DSC06083.jpg)

CubedMural-ExhibitionCropped.jpg)

Renee-Richardson-headshot.-Music-Alumna-(1).jpg)

Alyssa-LeeNASA-1-(2).jpg)

RacineFranks2018.jpg)

20171117_Communications_TV_Production_Class_01.jpg)

-stock-img-bridge.jpg)

Pensacon-3Dprints.png)

024-c.jpg)

UWF-English-Professor-Jon-Fink.jpg)

20180205_Typewriter_Project_018.jpg)

28227057299_92a1d6bfa6_k-(1).jpg)

20180116_Seligman_First_Amendment_Lecture_Series_007.jpg)

20170512_CASSH_Forensics_010.jpg)