Suzanne Lewis, National Park Service • UWF Alumna ’78

One for the history books.

Suzanne Lewis was not only the first female superintendent of one national park—but five. Her 32-year career to preserve and protect our national treasures has made modern-era history.

“I never planned to be a park ranger.”

By Mark Gause

From sparkling emerald waters, magnificent white beaches, and brick and mortar fortresses to hot springs, snow-covered plateaus blanketed with bison and a world-famous geyser, Suzanne Lewis’ trek has gone from sea level through acres of wilderness and glacier-carved valleys to icy peaks more than 10,000 feet high.

Saying Lewis’ career soared to record heights and broke new ground would be a bit of an understatement. But when you ask for her perspective on what most of us would see as a phenomenal life and career, Suzanne modestly responds that it was an honor to play a small part in preserving these great treasures.

In order to fully understand and appreciate the trail that Suzanne has blazed, you need to step in her proverbial shoes—a pair of sturdy hiking boots.

Suzanne was born in West Virginia and grew up in Ohio. Her family moved to central Florida prior to Suzanne’s sophomore year in high school—one year before Disney World opened and made a magical mark on Florida’s history. After graduating from Seminole High School in Sanford, Florida, she followed the advice of a couple friends and drove to Pensacola to check out the University of West Florida.

She found the campus to be quaint, open and welcoming—atypical from other Florida universities. She was smitten, but also saw it as “sea level rise.” She was going to either sink or swim. For someone like her, who didn’t grow up with much and was the first in her family to attend college, she relied heavily on financial aid, scholarships and the work-study program to make her way. Suzanne enrolled as a pre-med major, but quickly figured out that she didn’t have the acumen for it and changed to a history major.

To this day, Sissy—as her dad fondly called her—remembers his less than enthusiastic response to the news. It was one of those classic dad retorts; “What are you going to do? Open a store and sell history by the pound?” What her dad didn’t know was that the demand would be by the acre. Over 3 million acres of the most pristine and protected parcels of land in America.

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

— A favorite quote from Suzanne’s favorite book, “David Copperfield,” by Charles Dickens

Suzanne never planned to be a park ranger, but she graduated from UWF on a Saturday and started Sunday at the Gulf Island National Seashore. From there, her career caught fire, which is a phrase that rangers in the National Park Service aren’t fond of using (apologies to Smokey the Bear). Suzanne advanced to park ranger, district ranger, superintendent and senior executive service (SES) official—an impressive feat since there are hardly a dozen SES in the country, only three of which are female.

Suzanne’s distinguished and historic career of 32 years is punctuated by becoming the first female superintendent for five national parks:

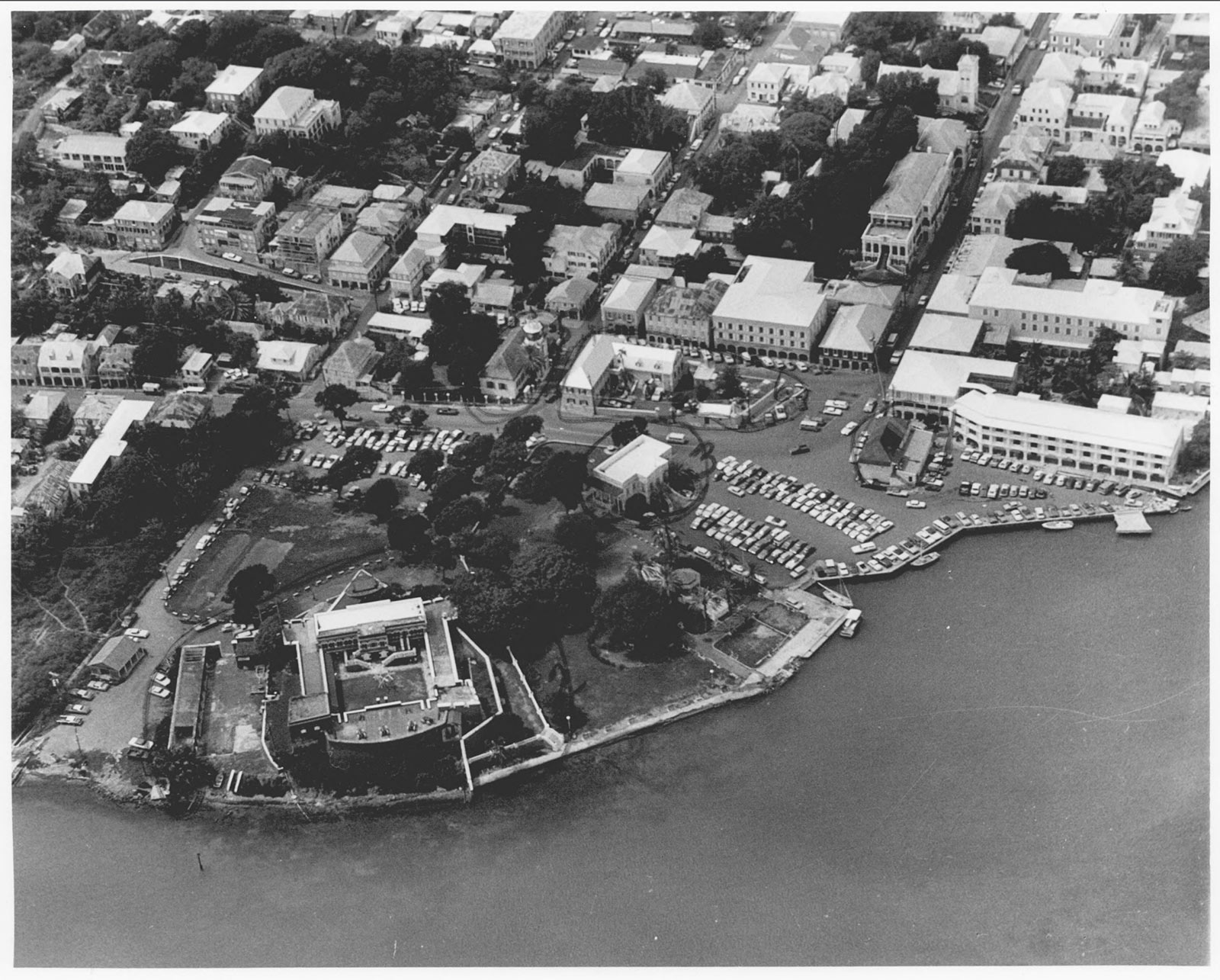

- Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve along with Fort Caroline National Monument in Jacksonville, Florida

- Christiansted National Historic Site, Buck Island Reef National Monument and Salt River Bay National Historic Park in the U.S. Virgin Islands

- Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area in Georgia

- Glacier National Park in Montana

- Yellowstone National Park, the oldest national park in the country

Suzanne’s passion for preserving and protecting land and history extended past her impact in the U.S., reaching internationally to countries all over the world. One such trip was a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization project in Haiti, which is the only other country besides the United States to win independence from a colonial power. The project was to preserve a historic fort as a World Heritage site. This site was on the north end of the island, near Cap-Haïtien, high in the mountains. It was a rough climb. Once onsite, Suzanne showed the Haiti people how to repoint and relay the brick, fortifying the fort and ensuring it remains a piece of Haiti’s history for decades to come.

Another trip took Suzanne to Sweden to offer assistance with the management of brown bears—the same species as our grizzlies except large male brown bears routinely weigh over 1,000 pounds in the fall when gorging themselves on fish. During this trip, Suzanne hiked up to a glacier lake and stepped into Norway at sunrise. Suzanne remembers it as the most spectacular and stunning sight, watching the sun rising up above the fjords.

Suzanne spent six years acquiring land for U.S. national parks, totaling 46,000 acres. She was able to partner with the state of Florida in 1991 to secure the donation of the Kingsley Plantation, a historical landmark rich with artifacts that share Florida’s history of slave ownership. Acquiring it as part of the Timucuan Ecological and Historical Preserve was a huge accomplishment.

It would be great if all tough decisions were celebrated, but some can be pretty political. Suzanne was invited to testify to Congress on multiple occasions. One of the more memorable times was a field hearing concerning snowmobiles in Yellowstone. It was a contentious issue because access to the park for snowmobilers had been under regulated and caused unacceptable impact to the park resources. But in response to an Environment Impact Study, the new policy reduced and highly regulated the number of snowmobiles in the park. The once endless season and 24/7 access was changed to a limited season with no more than 500 guided snowmobiles per day.

Suzanne acknowledges that all National Park Service jobs are pretty stressful jobs because the people are so highly dedicated to the mission of the park service and so passionate about what they do. She understands that being the oldest national park, most everything happening at Yellowstone is highly charged and put under a microscope. Suzanne also knew that being the Yellowstone Superintendent would be controversial. But not until she started dealing with the angry emails and death threats did she know exactly to what degree. Suzanne grew thick skin quickly, and being a natural leader, found her footing and the best way to navigate around the rocks and arrows hurled in her direction. As Suzanne recounts, “you’ve got to be able to self-assess and move forward. No matter how hard it is or how often the New York Times calls for you to be fired.”

But the difficult times Suzanne experienced were far outnumbered by the good. During her tenure as Glacier National Park Superintendent, Suzanne was named “Flying Eagle Woman” by the Blackfeet tribe in a naming ceremony at Waterton Lakes in 2001. She was also honored by the National Audubon Society with the 2010 Rachel Carson Award for her contributions to conservation—the first National Park Service employee to receive the award. The Audubon has been recognizing outstanding women in conservation with this award since 2004.

There have been a number of notable women who have impacted and influenced Suzanne’s historic journey. At UWF, Dr. Elizabeth Hardwicke, the professor of Ancient Civilization & Byzantine History, was like no other woman Suzanne had encountered before. Cultured, scholarly and a product of the Stanford Fellowship program, Dr. Hardwicke had high expectations and academic standards for her students, but was equally warm and nurturing. Dr. Hardwicke invited poorer students to her home who needed nourishment for the body as well as the mind. This wasn’t an uncommon occurrence. Likewise, Dr. Mary Rogers, a professor of Sociology, was a phenomenal woman, outgoing, a great cook and champion of young women. Dr. Rogers helped to build female students’ confidence by reaching them on a personal level to find their best self. Both of these professors made college a fuller and deeper experience.

None of which was more transformative than the first day and first class at UWF—Dr. Hardwicke’s Ancient Civilization class at 9 a.m. in Building 11 (Suzanne still has the textbook). Upon entering the classroom, Suzanne saw someone in jeans and a denim shirt, like her so she pulled up a seat next to Rulaine Kegrerreis, who was also a history major. The innocent decision to take a seat by Rulaine was written in the stars. Rulaine’s dad was a park ranger at Gulf Island National Seashore, and encouraged Suzanne to become a seasonal worker at the park. That work as a new graduate opened up a new world of possibilities, inspiring her long and fruitful career. As for Rulaine, she worked more than 30 years with Eastern National, a nonprofit organization which just happens to manage and serve visitors at the bookstores in our national parks. The two women have been lifelong friends ever since—sharing a passion for these great national treasures and the history woven into each park.

Suzanne retired in 2011, but continues to pursue her passion and dedication to public land preservation programs through her work with the Sonoran Institute in Tucson, Arizona as well as being on the board of directors for the UWF Historic Trust. Suzanne was also appointed to the UWF Board of Trustees in 2012, coming full circle to contribute to the institution that launched her into a life of discovery, leadership and service.